New Yorker writer Michael Specter, on his first visit to a chicken farm:

"I was almost knocked to the ground by the overpowering smell of feces and ammonia. My eyes burned and so did my lungs, and I could neither see nor breathe….There must have been thirty thousand chickens sitting silently on the floor in front of me. They didn’t move, didn’t cluck. They were almost like statues of chickens, living in nearly total darkness, and they would spend every minute of their six-week lives that way."

—Michael Specter, New Yorker, April 14, 2003.

The vast majority of chicken meat we find in grocery stores and restaurants comes from “broiler” chickens intensively confined on “factory farms.” Each year in the United States, more than 8 billion chickens are raised on these farms. These chickens suffer both acute and chronic pain due to selective breeding, confinement, transportation, and slaughter.

According to one study, 90 percent of broilers had detectable leg problems, while 26 percent suffered chronic pain as a result of bone disease. Two researchers in The Veterinary Record report, “We consider that birds might have been bred to grow so fast that they are on the verge of structural collapse.” Industry journal Feedstuffs reports, “Broilers now grow so rapidly that the heart and lungs are not developed well enough to support the remainder of the body, resulting in congestive heart failure and tremendous death losses.”

Broiler chickens are confined in long warehouses, called “grower houses,” that typically house up to 20,000 chickens in a single shed at a density of only 130 square inches of space per bird. Such stocking densities make it impossible for most birds to carry out normal behaviors and cause the chickens to suffer from stress and disease. As two industry researchers write, “Limiting the floor space gives poorer results on a bird basis, yet the question has always been and continues to be: What is the least amount of floor space necessary per bird to produce the greatest return on investment.”

After the industry average of 45 days in the grower shed, chickens are transported to slaughter without food, water, or shelter from extreme temperatures. At the slaughter plant, the chickens are dumped onto conveyors and hung upside down in shackles by their legs. In the United States, there is no legal requirement that chickens be made unconscious before they are slaughtered. Birds have their throats cut by hand or machine. As slaughter lines run at speeds of up to 8,400 chickens per hour, mistakes are common and many birds are still conscious as they enter tanks of scalding water.

Standard industry practices cause chickens to experience both acute and chronic pain. The treatment of these animals would be illegal if anti-cruelty laws applied to farmed animals. But, profits have taken priority over animal welfare. As one industry journal asked, “Is it more profitable to grow the biggest bird and have increased mortality due to heart attacks, ascites, and leg problems, or should birds be grown slower so that birds are smaller, but have fewer heart, lung and skeletal problems? A large portion of growers’ pay is based on the pound of saleable meat produced, so simple calculations suggest that it is better to get the weight and ignore the mortality.”

Selective Breeding

The vast majority of chicken meat we find in grocery stores and restaurants comes from “broiler” chickens intensively confined on “factory farms.” Each year in the United States, more than 8 billion chickens are raised on these farms. These chickens suffer both acute and chronic pain due to selective breeding, confinement, transportation, and slaughter.

In the 1950s, it took 84 days to raise a five-pound chicken. Due to selective breeding and growth-promoting drugs, it now takes an average of only 45 days. To put the growth rate of today’s chickens into perspective, the University of Arkansas Division of Agriculture reports, “If you grew as fast as a chicken, you’d weigh 349 pounds at age 2.” While this rapid growth increases profitability, it also aggravates health problems among chickens.

The leading health problem caused by fast growth is the high rate of leg disorders causing crippling lameness. Broilers’ bone growth is outpaced by the growth of their muscles and fat. In one study of lame chickens, 20 percent had bacterial infection of the bone, 13 percent had visible leg deformities, 11 percent had spondololisthesis (slipped vertebra typically caused by degenerative spinal disk disease), and 11 percent had tibial dyschondroplasia (a condition characterized by an abnormal mass of cartilage preventing normal bone development, which may lead to bone fragility, distortions, and infections). Another study estimated 30 to 49 percent of broilers suffer from tibial dyschondroplasia. One study found that 90 percent of broilers had a detectable abnormality in their gait. These deformities are known to be painful. One survey found that 26 percent of broiler chickens were suffering chronic pain in the last weeks of their lives as a result of bone disease. Another researcher concluded, “Broilers are the only livestock that are in chronic pain for the last 20% of their lives. They don’t move around, not because they are overstocked, but because it hurts their joints so much.”

Lameness causes many chickens to be unable to support their own weight. At six weeks, broiler chickens have such difficulty supporting their abnormally heavy bodies that they spend 76 to 86 percent of their time lying down. This, in turn, leads to breast blisters, burns, and foot pad dermatitis. Contact dermatitis due to lameness has been shown to affect up to 20 percent of broiler chickens. Because sheds are not cleared of litter and excrement until chickens are taken to slaughter, the birds have no choice but to stand in their own waste. As a result, bacteria often infect skin sores, leading to disease.

Severe leg deformities are fatal if birds can no longer stand to reach food or water. One to 2 percent of all birds die due to leg problems. One group of researchers concluded, “We consider that birds might have been bred to grow so fast that they are on the verge of structural collapse.”

In addition to lameness, intensive breeding for genetic selection has caused broiler chickens to suffer from respiratory disease, coccidiosis (a parasitic infection resulting in sometime fatal blood loss), inclusion body hepatitis, leg weakness, big liver spleen disease, acute death syndrome, and ascites. Broilers selected for faster growth suffer from weakened immune systems, making them more susceptible to a variety of diseases.

In acute death syndrome (ADS), chickens suddenly lose their balance, violently flap their wings, go into spasms, and die. Between 1 and 4 percent of broilers may die of ADS. The syndrome is a form of acute heart failure caused by fatal arrythmias, which are common in broiler chickens and have been linked to their rapid growth rate.

Another typical condition among broilers is ascites, in which the heart and lungs do not have sufficient capacity to support an overgrown body. Ascites is responsible for 5 to 12 percent of mortality in broilers. An industry journal reports that “broilers now grow so rapidly that the heart and lungs are not developed well enough to support the remainder of the body, resulting in congestive heart failure and tremendous death losses.” Heart failure is taken less as an indicator of poor breeding and more as a sign of optimal production. As one chicken farmer wrote, “Aside from the stupendous rate of growth...the sign of a good meat flock is the number of birds dying from heart attacks.”

Despite the health problems described above, producers continue to breed birds for fast growth. One study found that selection against leg disorders came only ninth out of 12 factors taken into account by the breeders of broilers, with growth rate and feed efficiency being first and second.

Confinement

Chickens are the most intensively confined of all farmed animals. Broilers are warehoused in long sheds, called “grower houses,” which typically confine up to 20,000 chickens at a density of approximately 130 square inches of space per bird. Such densities make it impossible for most birds to carry out normal behaviors. A chicken requires 138 square inches just to stretch a wing, 178 inches to preen, 197 to turn around, and 291 to flap her wings. As one researcher put it, “ It looks as though there is white carpet in the sheds—when the birds are fully grown you couldn’t put your hand between the birds, if a bird fell down it would be lucky to stand up again because of the crush of the others.”

The high stocking density within the sheds also frustrates chickens’ natural social behaviors. Space is used by animals in a social context to position themselves appropriately in relation to each other. Chickens have a carefully regulated social life and a cohesive social group structure. When crowded, their social system breaks down, and they have been found to be in a chronic state of stress.

In addition to overcrowding, the number of birds in grower sheds disrupts the social structure of chickens. In groups of several dozen birds, such as those found naturally in the wild, chickens can establish a social hierarchy. But when housed with thousands of other birds, establishing a social hierarchy becomes impossible, resulting in a higher frequency of aggression towards one another. The social chaos increases competition for resources, which may result in starvation or dehydration for weaker birds.

Grower houses are commonly windowless and force-ventilated to control temperature. They are barren except for litter material on the floor and rows of feeders and drinkers. Such an environment prevents chickens from practicing many of their natural behaviors, including nesting and foraging. This deprivation is believed to frustrate broilers and decrease their welfare.

Overcrowded confinement also results in the rapid deterioration of air quality within the grower sheds. As the weeks pass, chicken excrement accumulates on the floors. As bacteria break down the litter and droppings, the air becomes polluted with ammonia, dust, bacteria, and fungal spores. High ammonia levels cause painful skin and respiratory problems in the broilers, as well as pulmonary congestion, swelling, hemorrhage, and even blindness. Ammonia destroys the cilia that would otherwise prevent harmful bacteria from being inhaled. As a result, chickens “are inhaling harmful bacteria constantly” and develop respiratory infections, such as airsacculitis. To minimize these problems, ammonia levels should not exceed 20 parts per million. However, actual ammonia levels regularly exceed this amount. During the winter, when ventilators are closed to conserve heat, ammonia levels may be as high as 200 parts per million.

Chickens have an acute sense of smell they use to perceive their environment. Ammonia fumes inhibit this sense. As one animal scientist put it, “For a bird with an acute sense of olfaction the polluted atmosphere of a poultry house may be the olfactory equivalent of looking through dark glasses.”

In such overcrowded conditions, factory farmers accept that many chickens will die from disease and stress. But there remains an economic rationale for farms to overcrowd the birds. “Limiting the floor space gives poorer results on a bird basis, yet the question has always been and continues to be: What is the least amount of floor space necessary per bird to produce the greatest return on investment.”

Transportation

After an average of 45 days in the grower sheds, broiler chickens have reached market weight and are ready to be taken to slaughter. The birds are caught by the legs and thrown into crates. Catching teams load crates at rates of 1,000 to 1,500 birds per hour. Many chickens are injured in the process, suffering dislocated and broken hips, legs, and wings, as well as internal hemorrhages. As one researcher described, “Hip dislocation occurs as the birds are carried in the broiler sheds and loaded into the transport crates. Normally the birds are held by one leg as a bunch of birds in each hand. If one or more birds start flapping, they twist at the hip, the femur detaches, and a subcutaneous haemorrhage is produced which kills the bird....Dead birds that have a dislocated hip often have blood in their mouths, which has been coughed up from the respiratory tract. Sometimes this damage is caused by too much haste on the part of the catchers.”

Once the crates are packed onto trucks, the chickens are transported to the slaughter plant. One group of researchers concluded, “Chickens find transport a fearful, stressful, injurious and even fatal procedure.” A number of studies have discovered high levels of stress hormones in the blood of chickens during transport. During transport, broiler chickens are denied food, water, and shelter from extreme temperatures. According to one scientist, “Unless crates are properly covered, exposure to wind and cold will rapidly cause freezing of unfeathered parts. The frosted appendage first becomes red and swollen, followed by gangrene, necrosis, and sloughing.” Many chickens die during the trip from hypothermia or heart failure associated with the stresses of catching and transport

Slaughter

At the slaughter plant, the chickens are moved out of the trucks, dumped onto conveyors, and hung upside down in shackles by their legs. Shackling is painful for chickens, especially since so many suffer from bone and joint problems. One group of researchers concluded that “90 percent of broilers had a detectable gait abnormality indicating leg weakness, and 26 percent suffered an abnormality so severe that their welfare was considered compromised. This level of leg abnormality, if representative of commercial flocks, provides evidence that, potentially, a large number of birds should not be shackled.” One study found that, after shackling, 3 percent of broilers had broken bones and 4.5 percent had dislocations. Another study found a 44-percent increase in newly broken bones following shackling.

In the United States, poultry are not included under the federal Humane Methods of Slaughter Act, thus there are no legal requirements that chickens be made unconscious before they are slaughtered. Electric stunning is often used to immobilize chickens before slaughter, making them easier to handle. However, the voltage used may be insufficient to induce unconsciousness.

Birds then have their throats cut by hand or machine. Failure by workers or machines to cut both carotid arteries can add two minutes to the time taken for birds to bleed to death. As slaughter lines run at speeds of up to 8,400 chickens per hour, many workers miss these arteries and most machines are not even designed to cut them properly. One researcher concluded, the “problems associated with inefficient neck cutting [are] only too common in poultry processing plants.” As a result, birds may be conscious as they enter tanks of scalding water intended to loosen the birds’ feathers. One study found that up to 23 percent of broilers were still alive when they entered scalding tanks.

Broiler Breeders

Each year in the United States, approximately 60 million broiler chickens are used to breed other broilers. These “breeders” have the same genetic predisposition as other broilers for fast growth, lameness, and heart disease. If, like factory-farmed broilers, they were fed on unrestricted diets, only 20 percent would survive to sexual maturity. Likewise, breeders are fed as little as a quarter of the amount of food they would otherwise eat. Food restriction is believed to cause “general undernourishment, specific nutritional deficiency, and frustration.” The European Commission’s Scientific Committee on Animal Health and Animal Welfare concluded that “current commercial food restriction of breeding birds causes poor welfare.”

Broiler breeders undergo a series of mutilations meant to reduce side effects of intensive confinement, such as disease and aggression. A portion of their beaks and toes are cut off, and males also have their combs and leg spurs removed. These mutilations are performed without anesthetic and are believed to cause both acute and chronic pain.

To control the age of sexual maturity and reduce costs, producers may limit the amount of light breeders receive to as little as six hours per day. This darkness causes stress and frustration among birds, and increases the incidence of blindness, which can reach 30 percent.

As a result of these and other insults to their welfare, breeders suffer from a variety of diseases and injuries during their lives. One study found that 92 percent of male breeders had pelvic limb lesions, 85 percent had total or partial rupture of ligaments or tendons, 54 percent had total ligament or tendon failure at one or more skeletal sites, and 16 percent had total detachment of the femoral head

Conclusion

Standard broiler industry selective breeding, confinement, transport, and slaughter practices cause chickens to experience both acute and chronic pain. For producers, profits have taken priority over animal welfare, as birds are pushed beyond their physical limits and housed in conditions both unhealthy and unnatural. As two poultry researchers asked, “Is it more profitable to grow the biggest bird and have increased mortality due to heart attacks, ascites, and leg problems, or should birds be grown slower so that birds are smaller, but have fewer heart, lung and skeletal problems?....A large portion of growers’ pay is based on the pound of saleable meat produced, so simple calculations suggest that it is better to get the weight and ignore the mortality.”

Photo Gallery - Week One

COK investigators documented the conditions at factory farms and slaughter plants in the United States, including two of the largest poultry producers, Tyson and Perdue.

Chicks raised for meat start their lives hatching in incubators. They never once meet their mothers. Courtesy USDA.

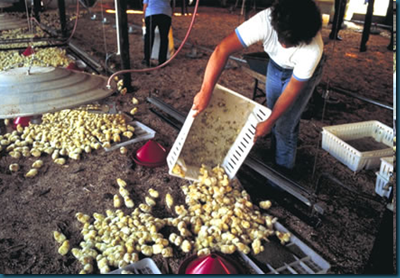

The chicks are transported in crates and boxes to factory farms where they will spend the next 45 days, the industry average for chickens reaching slaughter weight. Courtesy USDA.

Once inside the massive sheds on the factory farm, the chicks are dumped. Courtesy USDA.

Tens of thousands of chicks just days old are confined in warehouse-type sheds.

Factory farms are automated—from feed dispensers to mechanized waterers.

**********************************************************

Photo Gallery - Week Two

Although the sheds are cleared of birds once they reach slaughter weight, feathers and manure still litter the floor for the new inventory of chicks.

Due to selective breeding for rapid growth, many of the chicks are prone to leg disorders.

Crippled chicks with leg disorders—a result of selective breeding for rapid growth—commonly have difficulty walking and reaching the water dispensers and feeders. COK investigators offered water to dehydrated birds.

Despite being only days old, many chicks suffer from such serious leg disorders due to selective breeding for rapid growth that they have problems moving throughout the massive sheds. COK investigators provided aid to many of these crippled chicks.

Living in their own waste, the birds cannot escape the high levels of ammonia. As a result, their bodies are often scalded by the noxious chemical.

Birds on factory farms receive no individualized veterinary care and often die from illness and disease.

**********************************************************

Photo Gallery - Week Three

As the chicks grow, the free space in the shed decreases.

This chick has severe ammonia burns and cannot stand, let alone walk. She will either die from dehydration or have her neck broken by a worker.

Some chicks walk into the feeders, but not all are able to leave. Trapped inside the wires, these birds will die from dehydration.

Unable to leave the feeder, this chick died of dehydration.

Crippling leg disorders plague birds in the broiler industry. This chick cannot walk and is dying.

Unable to reach the water because of a leg disorder, this chick sits underneath the water dispenser.

**********************************************************

Photo Gallery - Week Four

With each passing week, the birds grow bigger and the free space in the shed gets smaller.

As sheds can hold tens of thousands of animals, the birds compete for water.

A COK investigator holds a dead bird. Her body is raw and burned from ammonia scalding after living for three weeks in the excrement of thousands of birds.

Factory farms are riddled with such filth, ammonia fumes, and other serious air pollution that breathing can be painful and difficult.

This bird, trapped in the wires of a feeder, struggled to free himself. Had COK investigators not removed him, he would have died from dehydration.

Crippled birds often cannot reach the water dispensers. Here, a COK investigator offers water to a thirsty bird.

********************************************************

Photo Gallery - Week Five

Selective breeding and drugs force the chicks to grow much faster than they would naturally. Severe overcrowding causes these one-month-old birds nearing slaughter weight to disrupt each other while moving through the shed.

This bird is trapped in a feeder, completely immobilized without any access to water.

A COK investigator offers water to this bird immobilized in the feeder. After drinking for several minutes, she was freed, but unable to walk.

Although COK investigators were able to provide aid to some birds, many were found dead throughout the sheds. This chicken's decomposing body still lies in the feeder where he was immobilized, unable to drink any water.

Chickens raised for meat fall victim to a high rate of leg disorders caused by intensive genetic selection for fast growth as well as growth-promoting drugs. This leading welfare problem not only results in painful crippling, it can prove fatal as some birds are unable to walk to food or water.

A leading welfare problem caused by intensive genetic selection for fast growth is the high rate of leg disorders.

By the fourth week, the floors of the sheds are littered with hundreds of corpses.

***************************************************

Photo Gallery - Week Six

Nearing slaughter weight, the birds have grown so large they take up virtually all of the floorspace in the shed. The overcrowding makes it difficult to move without disrupting other chickens.

With tens of thousands of birds in a single shed, competition for food and water can be intense.

Unable to stand due to crippling leg disorders and his massive weight, this bird had to prop himself up with his wing to avoid falling on his side.

This bird is decomposing into the litter.

**********************************************************

Photo Gallery - Week Seven

The birds—not even two months old—enter their last week of life.

Many of the birds suffer from ammonia scalding on their stomachs and breasts from lying in their own waste.

Chickens in the broiler industry suffer enormously. Severely overweight and many crippled, they lie throughout the sheds.

This bird's leg disorder makes moving—let alone walking extremely difficult. As factory-farmed animals do not receive individualized veterinary care, they are left to suffer without treatment or relief.

Just days before he would have been caught and trucked to slaughter, this bird died in the shed.

The factory farming of chickens for meat ignores animal welfare. It's difficult to believe this dead bird was less than two months old.

**********************************************************

Photo Gallery - Catching and Transport

Chickens are gathered three or four at a time, carried upside down by their feet. Their legs and wings often break in the process. Courtesy USDA.

Birds are sent to slaughter in multi-tiered transport trucks that do not have adequate protection from intense heat or cold. They are denied any food or water during the trip.

Once at the slaughter plant, the chickens are dumped onto conveyor belts.

**********************************************************

Photo Gallery – Slaughter

At the slaughter plant, the birds are hung upside down in shackles and their throats are slit.

Some birds miss the blades that cut their throats and enter scalding tanks while fully conscious.

After slaughter, the birds are beheaded and dismembered.

Watch the entire 12-minute video

Source: Compassion Over Killing

No comments:

Post a Comment